By Brian Richards | Film | January 7, 2022

Sidney Poitier — one of the greatest actors to ever appear on stage and screen, as well as the first African-American man to win an Academy Award for Best Actor — has died at the age of 94.

Born the youngest of seven children on February 20, 1927, Poitier lived in the Bahamas until he was 15 when he went to live with his brother’s family. At 16, he moved to New York City to work several jobs, including dishwashing. He would soon lie about his age in order to join the Army, and when he was granted a discharge in 1944, he would later audition for a role in an American Negro Theater production, which he got.

After an unsuccessful start in the theater due to being tone-deaf and unable to sing, Poitier would spend months working to perfect his craft and improve his career. This briefly paid off when he was given the leading role in Lysistrata on Broadway, which ended up closing after four performances but resulted in him working as a understudy in Anna Lucasta. In 1950, he made his feature film debut in No Way Out as a doctor who finds himself tested when two of his patients (Richard Widmark, Harry Bellaver) are a pair of brothers who are also armed robbers, one of whom dies from gunshot wounds, and the surviving brother blaming the doctor for not saving his life. The following year, he starred in an adaptation of Cry, the Beloved Country, and in 1955, he had a breakout role as Gregory Miller, a rebellious but musically talented student, in Blackboard Jungle.

In 1958, Poitier starred opposite Tony Curtis in one of their best-known films, The Defiant Ones, which told the story of two convicts chained together by their warden who escapes from custody and are forced to work together and trust each other to ensure their survival. It has been the inspiration for many action and crime films featuring two people of different races who hate each other but are forced to work together and who eventually end up liking/respecting each other, from 48 Hrs. to Black Mama White Mama to Lethal Weapon, and Fled.

The Defiant Ones received eight Oscar nominations, including Best Actor for both Curtis and Poitier, who became the first African-American man to be nominated in that category. Neither actor won, but Poitier did go on to win a BAFTA award for Best Foreign Actor, and a Silver Bear award at the Berlin Film Festival.

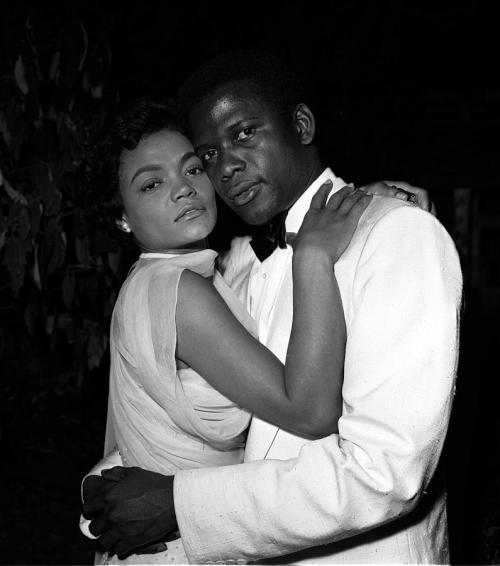

In 1957, he starred in The Mark Of The Hawk with Eartha Kitt, as a man who finds himself caught in the middle of hostility between British colonists and African villagers who want to reclaim their land.

In 1959, Poitier starred with Ruby Dee and Louis Gossett Jr. in Lorraine Hansberry’s play A Raisin In The Sun, which opened on Broadway and was then adapted into a film in 1961, with Poitier reprising the lead role of Walter Younger, who wants nothing more to gain wealth and success in order to improve his own life and the lives of his family in Chicago.

Poitier then appeared in Paris Blues, with Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Diahann Carroll, and Louis Armstrong. And in 1963’s Lilies of the Field, he played Homer Smith, a nomadic jack-of-all-trades who agrees to help a group of East German nuns build a new chapel. The film’s final scene is that of Homer once again teaching the nuns how to become more fluent in English, which then results in all of them singing the song “Amen.” As all of the nuns are singing, Homer pulls an Irish goodbye and leaves through the back door in order to continue his travels and go wherever the wind takes him. (The singing voice heard coming from Poitier isn’t actually his, as those vocals actually belong to the late actor/composer Jester Hairston, and if you grew up watching Nineties sitcoms in syndication, you’ll recognize Hairston as Rolly Forbes on Amen)

Thanks to this performance, Poitier would receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor, and when he won, he became the first African-American man to win this honor. (James Baskett, however, won an honorary Academy Award in 1946 for his role as Uncle Remus in Song Of The South)

In 1965, he starred in A Patch Of Blue with Shelley Winters and Elizabeth Hartman, and 1967 saw the release of three of the most successful films of Poitier’s career:

To Sir, With Love, in which he played an aspiring engineer who takes on a job as a teacher at a rough inner-city school.

In The Heat Of The Night, in which he played homicide detective Virgil Tibbs, who helps police chief Bill Gillespie (Rod Steiger) solve a murder investigation in Sparta, Mississippi despite the fact that they don’t like or trust each other. It is best remembered for Tibbs’ line, “They call me Mister Tibbs!” and for this one scene in which Gillespie and Tibbs are questioning a plantation owner named Endicott, who doesn’t appreciate being questioned like he’s a suspect, and who really doesn’t appreciate being questioned like he’s a suspect from someone who looks like Tibbs. (Poitier would later reprise the role of Virgil Tibbs in They Call Me Mister Tibbs! in 1970, and in The Organization in 1971)

I know that time travel wouldn’t be safe at all for anyone who isn’t white or male, but if I actually could time travel and do it safely, I would’ve loved to be at a movie theater showing In The Heat Of The Night on opening weekend just to see the reactions from Black audience members in the crowd when Sidney Poitier slapped that old white man in the face.

And Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, with Spencer Tracy, Katharine Hepburn, and Katharine Houghton (who is Hepburn’s niece), about an interracial relationship between a Black man and a white woman, and what happens when the woman brings the man to meet her parents.

In 1972, he starred with Harry Belafonte and Ruby Dee in one of the few Westerns that would feature Black actors in central roles: Buck and the Preacher, which was also Poitier’s directorial debut.

After starring in and directing A Warm December in 1973, Poitier would star in and direct Uptown Saturday Night, the first of four collaborations with Bill Cosby (I know, readers, I know), which also included Let’s Do It Again in 1975 (which is where The Notorious B.I.G. got one of his nicknames from), A Piece Of The Action in 1977, and Ghost Dad in 1990. (If you totally forgot that Ghost Dad was a movie that even existed, you’re not alone)

Poitier chose to focus on directing films instead of acting in them, and after directing the Richard Pryor/Gene Wilder comedy Stir Crazy, as well as Hanky Panky and Fast Forward, he returned to acting once again in 1988, when he starred in the film Shoot To Kill with Tom Berenger, Kirstie Alley, and Clancy Brown.

That same year, he starred in Little Nikita with the late River Phoenix. In 1991, he played NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall in the ABC miniseries Separate but Equal, which focused on the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education.

In 1992, Poitier starred with Robert Redford, Dan Aykroyd, River Phoenix, Mary McDonnell, David Strathairn, and Ben Kingsley in the beloved classic film that got me so many variations of “What the hell took you so damn long?!” on Twitter when I admitted to finally watching it for the first time last year: Sneakers.

His last feature film was as FBI Deputy Director Carter Preston in the 1993 film The Jackal with Bruce Willis and Richard Gere, though he would participate in documentaries such as A Century of Cinema, Wild Bill: Hollywood Maverick, Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey, Tell Them who You Are, and Mr. Warmth: The Don Rickles Project., and also appear in TV-movies such as Children Of The Dust, To Sir, With Love II, Mandela and de Klerk, David and Lisa, The Simple Life of Noah Dearborn, Free of Eden, and The Last Brickmaker in America.

Poitier also wrote three autobiographies: This Life, which was published in 1980, The Measure Of A Man: A Spiritual Autobiography in 2000, and Life Beyond Measure: Letters To My Great-Granddaughter in 2008.

Despite all that he accomplished in his career, Poitier also dealt with some judgment about those career choices. His characters were viewed by some as needing to be overly dignified and respectable with no visible sexuality or personality flaws anywhere in sight, and not allowing them to truly be as three-dimensional as they could be. This led many Black actors in his wake to feel as if they had two choices in the roles they took: they could either be like Poitier and play the respectful and safe Black man that wouldn’t give white people any reasons to be nervous or scared, or be the foolish and stereotypical comic relief who wouldn’t give white people reasons to be nervous or scared because they would embarrass themselves in order to make everyone laugh. This made Eddie Murphy’s role as Reggie Hammond in 48 Hrs. so groundbreaking back in 1982, as he made it very clear that he had a personality, an attitude, and a sex drive, and his concern with putting white people at ease was damn near nonexistent (particularly in the scene where he walks into a country-western bar and pretends to be a cop in order to get some crucial information).

But these concerns about Poitier and his choice of roles doesn’t change what he was able to accomplish, as well as the impact of those accomplishments. He made it possible for audiences everywhere of all races to not only recognize his own talent with nearly every one of his roles, but that of the many other Black actors who would appear onscreen with him, and who would go on to appear onscreen after him. Without Sidney Poitier and his work, there would be no Eddie Murphy, Mahershala Ali, Idris Elba, Jamie Foxx, Will Smith, Forest Whitaker, Samuel L. Jackson, Don Cheadle, Chadwick Boseman, and certainly no Denzel Washington, who has acknowledged the importance of Poitier and his legacy. He did so at the 2002 Academy Awards, during his acceptance speech when he won the Oscar for Best Actor for his role in Training Day.

And again during this recent Variety interview where he not only regrets not starring in a film alongside Poitier, but he waves off the idea that another Black actor needs to be the next Denzel Washington, which is similar to how the media used to proclaim Denzel as the next Sidney Poitier.

For years, there’s been speculation about who would take the torch from Washington, with [Chadwick] Boseman’s name on the shortlist. As journalists try to get behind the facade of Washington’s celebrity, his frowns are interpreted as disinterest, or a quip in response to a question is translated as a “bad mood.” Yet one of his endearing qualities is his willingness to love Hollywood despite its flaws. When asked about the Oscars’ omissions of “Ma Rainey’s” supporting men, particularly Colman Domingo and Glynn Turman, he responds: “I think they may have canceled each other out.”“What does the next Denzel mean?” Washington asks. “Does that mean there can only be one?” He lists actors such as Mahershala Ali and Jamie Foxx, who have defined themselves with their own successful careers. Washington smiles to himself, adding: “It doesn’t have to be one person.”

Throughout his lifetime, Poitier received many other awards and honors. He was awarded as Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II in 1974, the Kennedy Center Honor in 1995, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama in 2009. He is survived by his wife, Joanna Simkis, his six daughters (including Sydney Tamiia Poitier, who appeared in Veronica Mars and Joan of Arcadia), his eight grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

For all that Sir Sidney Poitier has accomplished, and for kicking open the doors for African-American actors so that their own talent could begin to be recognized and respected and acknowledged (though it goes without saying that there’s still a long way to go in that regard), I’ll end this tribute to Sir Sidney Poitier by simply saying thank you.

Thank you. And may you rest in peace.