Ode to Joy: Why Die Hard Is Still the Best Action Movie of the Modern Era

By Daniel Carlson | Guides | July 16, 2013 |

By Daniel Carlson | Guides | July 16, 2013 |

Twenty-five years on, it’s impossible to imagine what modern American action movies would be without Die Hard. It’s not just that it was a hit, earning $88 million domestically in the summer of 1988, equal to about $168 million today (and that it made that payday in an era before the bloated, hyper-budgeted tentpoles of the current comic book movie era). It’s not that it spawned four sequels of varying quality. It’s not even that it created a subset of action movie pitting one man trapped in an enclosed area against an army of increasingly dangerous enemies. Those things all happened, and they’re part of what made Die Hard legendary, but the film’s greatest success is that it showed us just how great a modern action movie could be. It casts a shadow over the genre because it stands as an example of how to tell a tight, exciting story with humor, suspense, and a kind of fluid grace that eludes almost every other action movie out there. After trying to crack different methods of looking at Die Hard — frankly, after being overwhelmed by how great it is and how much there is to talk about — I’ve decided to focus on three scenes that speak to different aspects of the film.

“Fists With Your Toes”: Setting the Stage

Die Hard is like a master class in the economics of storytelling. Everything works together perfectly, starting with the script from Jeb Stuart and Steven E. DeSouza and the direction from John McTiernan. McTiernan — also responsible for 1987’s Predator and 1990’s The Hunt for Red October, putting him pretty much at the epicenter of the era’s action movies — knows that the best way to keep a viewer hooked is to give them someone to root for and something to anticipate. Die Hard takes its time getting to the action sequences that would redefine the genre, but it does so in ways that are still smartly entertaining.

The opening scene is a perfect example. We open on John McClane (Bruce Willis) as he’s sitting in a plane, waiting for it to taxi safely to the gate. This is gonna be our guy, but he’s not some tank impervious to normal feelings or basic jitters. This isn’t Schwarzenegger. McClane’s first act in the film is one of nervousness and unease, and it takes a casual conversation with a fellow traveler to help him calm down. When the stranger tells McClane to go home and take off his shoes and socks and make “fists” with his toes as a way of shaking off the stress of the flight, McClane meets him with just the right mix of curiosity and amusement. “Trust me,” the guy says, “I’ve been doing it for nine years.” And then, once they land, we catch a glimpse of McClane’s gun as he reaches for his suitcase in the overhead compartment. He grins and says, “It’s OK. I’m a cop.” But he knows this doesn’t quite put the guy at ease, so he adds, “Trust me. I’ve been doing this for eleven years.” His cool evaporates when he grabs his package — a giant stuffed animal for his kids — and bumps into the flight attendant.

Establishing characters quickly, and doing so in a way that relies on visuals and normal dialogue instead of cheap exposition, is so hard to do. Think about how many times a character says something like “Mikey, you’re my brother, but you’ve just gotta” etc. etc., exactly like no one ever would in real life, just so we the viewers can be given the requisite cues to understand the story. But in just a few minutes, Die Hard has introduced their main character and shown him to be confident, flawed, resilient, humorous, and human. None of the dialogue feels out of place, and none of the interactions feel forced. The film’s tone — gritty but cocky, able to nimbly move between action and comic relief — is set up in an instant. No matter how many times you watch it, it still feels like a magic trick.

“She Never Heard Me Say ‘I’m Sorry’”: The Hero Alone

John McClane gets his ass kicked. A lot. In sharp contrast to the bulletproof slabs that powered through action movies of the 1980s, McClane is anything but invincible. McTiernan drives this home in the way the film expertly elevates the threat level as McClane fights his way through the horde of terrorists who have taken over Nakatomi Plaza. His first fight is just against one man, but it leaves him heaving and stumbling after they fall down a flight of stairs. Die Hard made it fashionable — practically mandatory — for action heroes to take their lumps. The best films that followed the Die Hard template always took time to show their hero struggling to stay in the game. Speed, which took the basic story idea and turned Nakatomi Plaza into a city bus, is a good example of this: its hero cop (Keanu Reeves) grows increasingly tired and frustrated, not to mention physically exhausted. I put it to you that it is not a coincidence that Speed’s director, Jan de Bont, was the cinematographer for Die Hard.

McClane’s low point comes late in the film, after a particularly brutal firefight that saw him walk across broken glass to escape. He’s tired, dejected, and trailing the thick dark jets of blood that signify some serious damage. He’s alone in a bathroom, picking shards of debris out of his feet and talking on the radio to Al (Reginald VelJohnson), his one remaining link to the real world, when he just starts to cry at the idea of never seeing his wife again. This is so crucial to what makes Die Hard work. It’s not just a story of a hero fighting a sea of bad guys, or even of a cop doing the thing he does best in an effort to save innocent people. It’s about a guy who wants to get home to his wife. The only reason he’s even there is to visit her and try to repair the leaning ruin of their marriage. The (mostly) nameless German hijackers don’t mean anything to him. The stakes are as high as they can possibly be in an action movie, which makes the action that much more grounded and realistic. McClane doesn’t want to kill these guys; he wants to do what he has to do to be reunited with his wife. That’s a vital difference.

“I Promise I Will Never Even Think About Going Up in a Tall Building Again”: Explosions in the Sky

Die Hard’s also, you know, an action movie, and an amazing one at that. McTiernan masterfully controls the ebb and flow of the film, building toward increasingly dangerous fights between McClane and the villains that have taken over the building. The first shot isn’t fired until 17 minutes into the film, and that’s just a single bullet. The villains silently glide in and take control of the building, waltzing quietly into the Christmas party at around the 23-minute mark. In other words, the film spends about a quarter of its screen time just getting things in place, and doing so in a way that emphasizes mood, character, and the real danger that’s to come. McTiernan moves up and down, crescendo and decrescendo, orchestrating the ideal action story. There are major, bloody battles, but there’s also the fantastically tense battle of words between McClane and Hans (Alan Rickman), the antagonist, about halfway through the film. After each battle, McTiernan gives the viewer time to recharge, and he also never lets his love of dazzling set pieces get in the way of the basic building blocks of the story. If you stripped out the action scenes and just watched everything else, it’d still make sense.

But who’d want to miss these action scenes? McTiernan directs with a flair rarely seen these days, and not just because he’s relying as much as possible on physical effects. He provides a real sense of space, a visual geography that lets you know exactly where you are even in the heat of the moment. As opposed to impressionist action films that want to bludgeon you into the idea of excitement by presenting you with a lot of bright blurs, McTiernan knows that the best way to excite a viewer is by actually taking them through the filmic space, whether that means swooping in on helicopters as they fire on the building or running alongside John McClane as he fights for his life. Over the course of the film, viewers become familiar with Nakatomi and its ins and outs, especially as McClane makes his way again and again through the same spaces in an effort to hunt or evade his enemies. (The first time McClane cuts through a floor that’s under construction, he sees some centerfolds that the crew have put up; the next time he passes by, he just nods and says “Girls,” both greeting them and orienting himself. We get humor, character, and helpful storytelling, all in one instant.)

That’s what makes the action so compelling, 25 years later: you feel it. Every shot, punch, explosion, shout, fall, flail, and wound. You actually see them all, buoyed along by McTiernan and de Bont. The editing from John F. Link and Frank J. Urioste is judicious, too, never wasting a moment but never chopping for the sake of it, either. Here are some numbers:

In other words, Die Hard is an action film that actually lets you experience the action. As a result, you don’t come away with the sense of being pummeled for two hours, but with memories of moments like John McClane’s jump from the roof of the tower. It’s a huge moment precisely because it’s allowed to be huge. It’s not competing with itself, fighting for your attention among a stack of random action scenes. This is the set piece that the whole film builds toward, and what a reward.

But what is Die Hard really? It’s a human story. It works so well — and holds up — because it excels at what we want movies to do. That is, it tells a story we can relate to, and it does it with style. Movies are the way we talk about who we are and who we wish we were, and the best ones always find a way to make us sit up and take notice of something that holds up a mirror to the world we’re going to face when the lights come up and we file out to the parking lot. These moments can happen in any genre or era; all that matters is that they happen. I will never in my life be in a situation like the one in Die Hard, but I know every bit of what it’s like to worry that someone you love is hurt or in trouble; to feel scared about the ways we drive ourselves apart; to hope that maybe this Christmas is the one where things turn around. Every great thing Die Hard does is done to serve this goal of making a human connection. It’s a thriller and an adventure, but it’s also the best kind of drama because it uses those grand fantasies as backdrops for an enduring story. At its base, it’s a fairy tale, a crusade about one man storming a castle. That story lasts because it always has.

Daniel Carlson is the managing editor of Pajiba and a member of the Houston Film Critics Society and the Online Film Critics Society. You can also find him on Twitter.

← 5 Shows After Dark 7/16/13 | 15 Great Performers Whose TV Shows Had An Embarrassingly Short Run This Year →

More Like This

Is the Video Game Industry Truly Rotten to the Core?

How To Help The Protestors On The Front Lines: An Incomplete List Of Places To Donate

Just In Time For The Holidays, It's Pajiba's Favorite Charities

The 2019 Pajiba Ten: The 10 Brainiest, Most Lustful Celebrities on the Planet

Should You See That Kevin Hart Movie, 'The Upside'? Take This Extremely Spoiler-Filled Quiz!

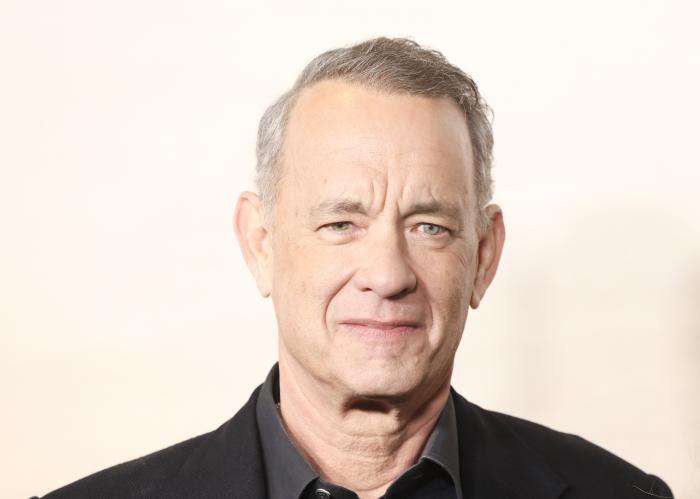

Tom Hanks Is Not Trying To Sell You Drugs

Three Trailers: What Happened Before Rosemary's Baby, and Zoe Saldaña In Her Own Skin

Jack White Threatens 'Fascists' In Donald Trump's Campaign With A Lawsuit

Taylor Swift Has a Brittany Mahomes Problem

'The Acolyte's Amandla Stenberg Got Thrown to the Wolves

Christina Aguilera Thinks It’s ‘Corny’ When Celebrities ‘Do Things Intentionally’ to Stay Relevant

Pajiba Love

Taylor Swift Has a Brittany Mahomes Problem

Reviews