By Petr Navovy | TV | February 16, 2023

I don’t think it’s ever taken me quite this long to figure out my opinion on a piece of media. I tend to be quite decisive about these things. Open-minded (I like to think), but decisive. With HBO’s The Last Of Us, however, I’ve been trapped sitting on the fence for five whole episodes. That’s unprecedented! I’ve speculated as to why that is before so I won’t clog things up here again.

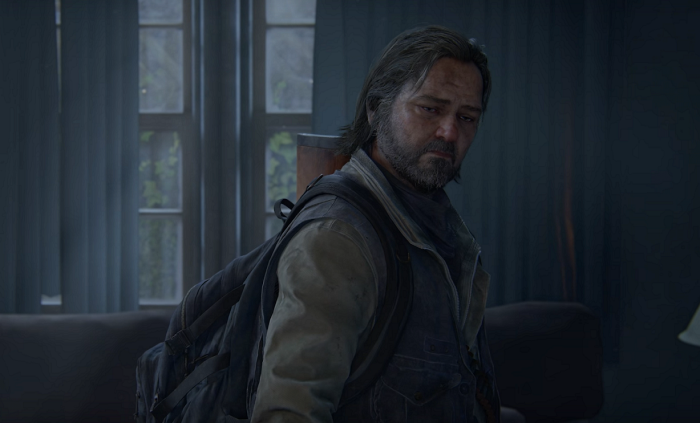

Since episode three I’ve been going back to re-watch the scenes from the game, and the realisation has dawned on me: I much prefer the way the game told this story. Episode three itself is an interesting case study as to why. That entry marked the first big departure from the game, expanding on the world by spending a significant amount of time with characters other than Joel and Ellie and filling out the backstory of someone who, in the game, is a relatively minor character, at least in terms of screen time. I won’t go into too much detail here as Tori already covered this in her excellent recaps, but in the game, the entirety of Frank’s storyline is communicated in a few lines and a few looks when Joel and Frank find a man’s body hanging from a noose in Bill’s town (very much filled with Infected in the game):

Joel: ‘What? Do you know this guy or something?

Bill: ‘Frank’.

Joel: ‘Who the hell’s Frank?’

Bill: ‘He was my partner.

Bill: ‘He’s the only idiot that would wear a shirt like that. He’s got bites. Here, and…’

Joel: ‘I reckon he didn’t wanna turn, so he…’

Bill: ‘Yeah. I guess not.

Bill: ‘Well, fu*k him.’

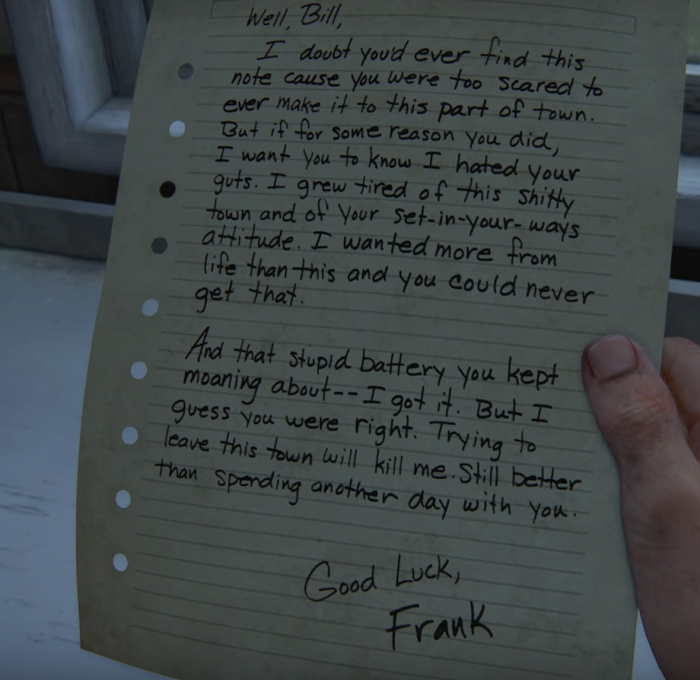

Later in that sequence, you find a note in the house, a letter that Frank left for Bill:

You have the option of showing this to Bill before you leave him. If you do, you notice a storm of emotions play out on his face and in his eyes in the fraction of a second despite his best efforts, but he composes himself quickly and hardens his shell again. An entire story plays out in your mind. In the show, of course, we get a 40-minute version of Bill and Frank’s history. It’s distinct in both tone and content. I like both versions. Both affected me emotionally for different reasons and in different ways. The show’s portrayal of what amounts to a happy ending in the world of the cordyceps served as an effective reminder of what there is to fight for in an otherwise bleak and hopeless landscape.

Yet it’s the game’s treatment of Bill and Frank’s story (or, rather, mostly just Bill’s) that gets to me. The abrupt and brutal nature of it ties in better with and reinforces just how barren human life has gotten—and as such underscores the potentially game-changing magnitude of Ellie’s unique gift, and of her and Joel’s mission. I’m not asking for misery p*rn here by any means, but personally, I’m finding myself less invested and getting less of an impact from the show because of some of these choices.

Though episode three made some changes that I could both see the positives and negatives of, it was the following two installments that cemented and expanded on my feelings of the show not living up to the game. In the fourth episode, one moment, in particular, stood out as a strong yet all too brief counterexample. When Joel and Ellie are ambushed as they make their way through Kansas City, they crash into the husk of an abandoned store, where a small group of men lay siege to them. Eventually, apart from the pair, there is one man left, wounded, on the floor, defenseless. Except once we get in close we see that he’s still much more of a boy than a man, at least in age. We know this situation can only end one way, and as the boy pleads for mercy Joel tells Ellie to go into the next room so she doesn’t have to see what has to be done. In his final moments, the boy cries for his mum, and it’s heartbreaking. In that instant, I remembered how the games made me feel, and I realized how infrequently the show is evoking that.

Joel’s violence is dramatically more pronounced in the game. So is that which occurs around him. It makes sense: Joel is only as brutal as the world has made him, and his violent acts are in the service of not just a potential cure for the plague that has brought the world low, they are also a natural manifestation of the primal need to protect that which he loves—a feeling that he thought he would never experience again after that world took it from him two decades earlier. I imagine the creative team behind the HBO show may well have sound reasons for toning things down (at least for now!), but so far it’s been pulling me out of the experience, and making the themes resonate less. I know I’ve said in earlier pieces that the heart and soul of this story is the relationship between Joel and Ellie, so it might seem odd to some that I’m moaning about the relative lack of violence, but it’s precisely that violence which is woven so deeply into every facet of their relationship.

Sam and Henry were another notable example of changes the show has made for the worse. Both actors were excellent in their portrayals of the brothers that Joel and Ellie meet on their way West, but by making Sam younger (he’s pretty much Ellie’s age in the game) and deaf, it came across to me as if the show was transparently trying to increase the sadness factor, and I felt manipulated rather than invested. Henry, too, is different in the game. The arc of his story with Joel and Ellie involves a more complex, ambivalent morality: At a key point during their escape from the city, after they have bonded and started to trust each other, Henry abandons Joel to near certain death. Later, they meet up again and Joel is not so quick to forgive. Henry remains unrepentant, at least on the outside. He says he knew Joel would make it, and he had to do what he needed to do to save himself and especially his brother. Despite all that, Henry remains a sympathetic character, and by seeing him make decisions that to some might seem selfish or wrong but which we understand given his situation and the state of the world he lives in, even more is done to immerse us in it. In the show, he tells us of morally difficult things he’s done, but we never see them, and he damns himself for them explicitly in a speech to Joel in a scene that again felt too nakedly manipulative. Henry taking his own life is more powerful in the source material too. The show did a good job of this gut-wrenching scene—with further praise needed for Lamar Johnson’s performance—but rather than lamenting what he has done, in the game Henry blames Joel for Sam’s death, his emotions a tempest of anger, sorrow, and blame as the world finally catches up to him and his brother. The end result of all these choices is that the show’s story has not rung nearly as true as the game’s for me.

I should add at this point that both Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey are doing a stellar job, and there are moments, such as Ellie’s whimper and expression when Henry turns the gun on himself, in which they fully drag me into their reality, and come close to making me feel like the game did. There are other elements of the show that are working to lessen the connection, however. Melanie Lynksey’s character for example—wonderful actor that she is—felt far too flippant and cartoonish in several of her scenes. Considering her background and the more raw moments that we see her in, I understand that this was probably a deliberate choice, but it didn’t work for me in the context of this world.

I’m fully conscious of the fact that I come to this adaptation of one of my favourite stories of all time with significantly loaded biases, but I’ve tried to keep my mind open as much as possible, and have delayed even letting myself assess what exactly I’m feeling about The Last Of Us as a show. Sadly, at the moment, I’ve come to think it’s not living up to what came before it.