Review: ‘Beastie Boys Story’ is the Story of a Life

By Seth Freilich | Film | May 4, 2020 |

By Seth Freilich | Film | May 4, 2020 |

There are several ways to look at the new documentary Beastie Boys Story.

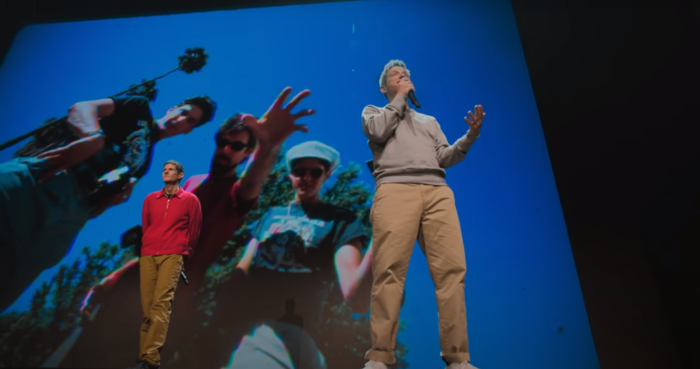

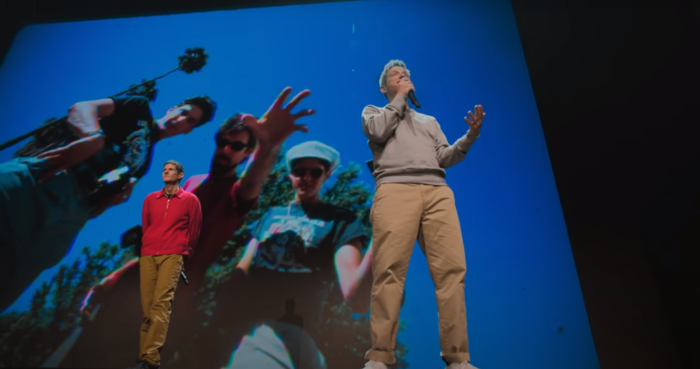

Of course, it’s a musical documentary about the career of the Beastie Boys, directed by close friend and music video collaborator Spike Jonze. The film’s “gimmick” is that it’s a film of a live stage presentation of the Beastie’s story, as told by the two surviving members, Mike Diamond (Mike D) and Adam Horovitz (Ad-Rock). In the early going, there’s an unnatural flow to the presentation, and I worried that this gimmick was going to wind up being a distraction. I didn’t settle into it until a moment where Mike and Adam pause in the mostly scripted storytelling to breakdown an early ’80s photo of Rick Rubin being shown on stage. This is when I realized one of the two advantages this theater approach has, which is that this is the kind of momentary magic you only get with a live show. It’s the kind of thing you would never get in a standard documentary where all the narration is provided as talking head pieces that by the nature of the craft can’t interact with the film’s subject matter the way these narrators can. At its best moments, the Beastie Boys Story is a more alive documentary than most because of this interactive element.

That aspect serves the film well because otherwise, as to the actual telling of the band’s story, there’s nothing remarkable here. It’s a well-told tale, and the film/show covers all the beats as well as can be done in a hundred minutes, moving relatively quickly and with purpose. If it wasn’t for this unique theatrical approach, it would feel like a very standard musical documentary. I don’t mean that as a dis, because sometimes a good story doesn’t need to be anything more than what it is. Fans of the Beasties, or good music documentaries, or even of fun theatrical presentations, they’ll all enjoy the film from that perspective alone.

But there’s another way to look at Beastie Boys Story, which is through the lens of the other story it’s telling, which isn’t really the story of a band, it’s the story of three boys who became men. It’s really telling the story of one of those men, the deeply missed Adam Yauch who passed away in 2012 (…eight years it’s been!?), who was the primary force responsible for all of them becoming men. From this perspective, it’s lovingly told and at its most affecting, as Roxana noted in Beastie Boys Story is a Love Letter to Moral Compass Adam Yauch:

All of that maturity, it seems, came from Yauch, and he is the guiding light of the Beastie Boys Story, its lighthouse, its North Star. …Sometimes it feels easy to romanticize people once they’re gone, but Mike and Adam pay homage to their friend and brother by sharing all that he cared about. By including photos from his world travels, by acknowledging that he quit the band in search of something deeper, by making clear that his grasp of what the group could do was what moved them forward.

(You should read that whole piece. It’s very on-point. I’ll wait for you to come back.)

This is another way in which the theatrical method of storytelling that Jonze uses also serves the story. It again takes something that is usually more static in a documentary and breathes in some life. Seeing Mike D. and Horovitz interacting with each other, and interacting with the memory of Yauch, there’s a warmth to it all. The love is clear. Their growth is clear. The two of them up there, very much in a settled down, dad joke mode, it’s all just warmth and quiet humility, with an edge of anarchistic humor. Which is exactly how Yauch would’ve wanted it. The story these guys are telling isn’t just the story of their band, it’s this deeply personal story of their dearly missed best friend. (And the pair are actually at their best when they’re telling stories or straight riffing, as opposed to several long monologues that are beautifully written but delivered in a way that feels … well … delivered).

But there’s one last way to look at a film like this, which is from a truly personal perspective. I don’t just mean subjective versus objective. Rather, bands have a personal connection with fans seemingly deeper and stronger than any other type of artist. And thus, many music documentaries play differently to audiences depending on how each of us views our connection with the band or their music. So here, casual fans may view this film simply as a music documentary about a band’s successes and missteps, while others may focus on the story arcs of growth and regression, the inherent human drama in every one of these tales. But because music can create such a personal connection, others may view it through a very specific, and very personal lens.

And that’s really how I watched Beastie Boys Story, from a deeply personal perspective, ultimately wanting to see if it validated or challenged the part I’ve always felt the Beastie Boys have played in my own story. The Beastie Boys are a band that I feel a personal connection with perhaps like none other. And while that is in part because of my love for their music, there are plenty of other bands who have music I love as much; it’s really because of that story arc about boys becoming men, a story that tracts and intersects with my own.

The Beastie Boys started as a punk rock gag that became unreasonably successful as caricatures come to life, an ouroboros snake eating its tail. But then they went away and came back as something different. Each time they came back, their music and their life view changed. They were increasingly more interesting, more retrospective, more mature. The part of that journey that went from “Licensed to Ill” through “Hello Nasty” happens to not only track my time from elementary school through college but also tracks my journey dealing with my mother’s death.

I was aware of the Beasties from an early time, as one of my friends had somehow gotten that early “Cookie Puss” EP they released. So I was already primed to love “Licensed to Ill” when it came out in the mid-’80s, and love it I did. Because I was a dumb little pre-teen who found the misogynist lyrics of “Girls” hilarious to rap on endless repeat in the basement, and you’re god damn right we gotta fight for our rights to party and listen to the little story they got to tell.

But three years later, my mother died and I very quickly was forced to mature out of a lot of that “dumb kid” shit.

Two days after that death, two days after I had my first taste of beer when an alcoholic neighbor didn’t know how to console a thirteen year old other than by giving him a beer, “Paul’s Boutique” was released and the Beastie Boys re-emerged with a newfound maturity. I don’t remember when I first heard the album — there’s a lot of haze, borne out of heartbreak and confusion, around that summer and fall — but it will forever be one of a favorite album because I’ve never forgotten what I felt listening to it back then. It was rich, and complex, and funny, and interesting. “Licensed to Ill” was a lot of things, but it wasn’t densely interesting like that. This “Paul’s Boutique,” it was so much more than what had come before it, and it planted this little seed in the back of my addled teen mind, this notion that change can be good.

Several years later, “Ill Communication” came out just before I graduated high school, and then the Beasties were silent until right after I graduated college, which they chose to celebrate by releasing “Hello Nasty.” Yet this story lives in the vacuum between those albums.

In the spring of 1998, the Dalai Lama made a trip to the United States, which included stopping at the Tibetan Buddhist Learning Center in New Jersey to deliver a reading. As Roxana noted in her piece, one of the many fascinating aspects of Yauch’s story was his journey to Buddhism, which led to the organization of the wonderful Tibetan Freedom Concerts. It’s no surprise that the Beastie Boys were at this reading. It is a random surprise that I was also there and that I was there because of the Beastie Boys.

I was taking a wonderful class at the time called Art, Gender, and Ritual, a seminar I joined primarily because I idolized the professor, Ruth (who became and remains a dear friend of mine). It wound up being the best class I took in college, not just because it expanded my understanding and appreciation of several things in such a way that it remains a guiding light for me to this day, but because it also had a very deep and meaningful import to me, which I’ve written a little about before. This was a class that introduced me to new aspects of women’s studies and art that a middle-class suburban white kid raised by a single dad was never going to have otherwise seen. It was also the first time I came to understand the strength and value of ritual and, as a result, understand one reason why religion is such a strong force in the lives of many (I was deeply agnostic at the time, only because I had not yet come to understand why I was really an atheist all the while). But it also meant so much to me because it was within the deeply private and personal space built by that class that I was able to come to proper closure with my feelings about my mother’s death almost a decade earlier.

Which brings me back to the Beatie Boys. Ruth was a member of the Religious Studies department, and someone in that department knew the Beastie Boys. He had been given four tickets by one of the Boys or their people to attend that Dalai Lhama reading, and those tickets made their way to Ruth, who decided to share the other three with some folks from our class because, hello ritual! I was fortunate enough to be one of the three invited to join.

So there I am, in a peaceful field on a quiet spring day, listening to prayers and beautiful words. Absorbing this atmosphere of quiet peace. Soaking in both the spirit and the surprising humor of the Dalai Lama. Thinking about the Beastie Boys because I love them so much and how weird is it that I’m here because of them. Thinking about all the rituals we studied in class and how this fits in with those, how rituals help you grow and heal. How they help you address death. How the Dalai Lama, a man of such peace in a world of such violence, manages to be so calm, sharp, and light-spirited. Thinking about Cindy Sherman, the woman among the many we studied who I found myself most drawn too, because of the cinematic flare, the deep story-telling, and the brave exposure of self she thrust into all her work. All of this is swirling in my brain like a pressure cooker and suddenly the valve is released and what’s left is The Idea — my final exam project is going to be a Cindy Sherman inspired ritual about my mother and her death.

At that time, I had acted on stage in front of hundreds of people and I had given speeches to over a thousand people. Yet just weeks after that Dalai Lama reading, I found myself terrified about getting up in front of just 13 people. Because talking to people, or performing in front of people, that’s easy. Exposing yourself, opening yourself up so deeply when you have no idea how it’s going to be received, and what’s coming back to you — that’s terrifying. In retrospect, that’s a large part of exactly what the journey of Yauch and the Beasties Boys was, right? Going from mere performers to men sharing and trying to be of one with their audience. But back in that class, I wasn’t thinking about that. I was just thinking I have to get up there and get through it.

And I did. I have never talked about the actual ritual/presentation to anyone and I never will. The central physical component of that project was accidentally destroyed by my college girlfriend’s mother a week later, and this wound up being fortuitous because there’s a part of me that likes that this thing only lives in that space from decades ago and that only those thirteen people I shared that moment with will ever truly know it. But what I will tell you is that I fucking cried hard, and it was cathartic. It was when I was done that the real heart of this story for me kicks in. It’s the part that I still tear up about, and I’m literally typing these words through glassy eyes.

See, what I didn’t mention is that I started that class two weeks after everyone else (with a special exemption from Ruth because this type of seminar normally did not allow late joining). So I rolled into what was a very private and intimate space to see eleven girls and one other guy, a group that all happened to know each other already, so there was a comfort among them. But nobody knew me, and they definitely weren’t comfortable with what they saw walk through the door (trench coat, shoulder-length hair, a buff, Matrix-sunglasses a year before that movie came out — you can’t blame them, I looked a mess). After class, two of the girls went up to Ruth and asked her to kick me out of the class because the way Ruth has presented what this seminar’s journey was going to be like, they wanted a safe space and who the hell was this mother fucker that just came barging in. She asked them if they trusted her, and they said they did, and she simply said, “Well, then trust me.”

After I finished my ritual/presentation through tears, a girl came up to me and hugged me. She looked me in the eyes afterward, and through her own teary eyes, said something to the effect of “I’m sorry. I tried to get you kicked out of the class and that was dumb. And I’m sorry.” Now I already knew this — Ruth had told me the whole story a few weeks earlier — and I never held it against her or the others, never wanted, expected, nor needed any apology. Yet that “I’m sorry.” God damn, it completed the job of wrecking me. For one thing, my emotions tend to be their strongest in moments of empathy. Seeing someone die in a movie doesn’t get me, but seeing others react in their grief, that gets me every fucking time. So my sadness up there at that moment, that was one thing. But then this other person’s sadness and release, while I’m there as open and exposed and raw as I’ve ever been, man that hit hard. And then, somewhere in the back of my brain, the Beastie Boys came back into the picture. This band that was there when my mother died, this band that inadvertently helped me get to this moment of final peace with the same, their whole god damned story was about being more than what they looked like. And here’s this woman saying, essentially, “I’m sorry, and I’m glad you turned out to be more than you look like.”

And so some thousand words later, that brings this back around to the question I came into the movie with. From the personal perspective, does this validate my understanding of the Beastie Boys or challenge it, and what does that mean for my story? And the truth is, of course, that it doesn’t matter. Yes, the film mostly fits in with what I’ve always understood and believed about Yauch and the Beasties, and when Horovitch has to hand one part of the story over to Mike D because his emotions get to be a bit too much, well that had me tighten up in a wave of sadness and remorse that feels both painful yet strangely comforting. It was at that moment that a lot of my personal story that I spun above came rushing back to me.

But as Horovitch also notes, in talking about the gig that they did not know would be their last gig, “things never come full circle, they’re hexagonal.” There is no closing of the circle here. Beastie Boys Story is just another part of their story and, as such, of mine. In one of the last tracks on their last album (“Hot Sauce Committee (Pt. 2)”), Yauch raps: “The odds are stacked for those who lack, been a lucky motherfucker when it comes to that.” And more than anything, Beastie Boys Story reminds how lucky we were to have the Beastie Boys and Adam Yauch.

You can watch Beastie Boys Story now on Apple TV+.

← One Month On From Its Launch, How Has Quibi Disappeared From Public Conversation So Quickly? | Do We Really Need a 'John Wick' Spin-Off, Plus Is 'New Mutants' Finally Going Straight to VOD? →

More Like This

Kyle Mooney's Horror-Comedy 'Y2K' Goes Too Hard on Kyle Mooney's Sense of Humor

'Imaginary' Almost Sucks

Box Office Report: Kung Fu Sandworms

The 2024 Oscars Were Great Right Up Until the End

Kristen Stewart's 'Love Lies Bleeding' Is Gonna Kick Your Ass And Make You Beg For More

What’s Old Is New Again: Old Hollywood Glamour Glitters at the 2024 Oscars

Al Pacino Presents Best Picture Oscar, Confuses Everyone

The Dangerous Lie Of 'TradWives'

A Legendary Horror Franchise Is Headed To Television

'The Mandalorian' Season 4 Is Probably Not Happening

Halle Bailey On Why She Chose To Keep Her Pregnancy Private

More Like This

Kyle Mooney's Horror-Comedy 'Y2K' Goes Too Hard on Kyle Mooney's Sense of Humor

'Imaginary' Almost Sucks

Box Office Report: Kung Fu Sandworms

The 2024 Oscars Were Great Right Up Until the End

Kristen Stewart's 'Love Lies Bleeding' Is Gonna Kick Your Ass And Make You Beg For More

Reviews