The Fetish of Trauma: Ten Years Later and ‘A Little Life’ Remains One of the Most Divisive Novels of the Century

By Kayleigh Donaldson | Books | May 16, 2025

Publishing trends are tough to predict. As with anything in pop culture, it’s near-impossible to guess where audience tastes will go. You can try to change the direction the wind is blowing but ultimately you cannot fake hype. Nobody expected a Twilight fanfiction to become a phenomenon and inspire a new mainstreaming of erotica. I never would have called the success of dark romance. Ten years later, it’s still a minor miracle that a 700+ page novel about the ceaseless trauma inflicted upon one gay man would be not only a bestseller but a wildly controversial leader of the zeitgeist and symbol of social media cool.

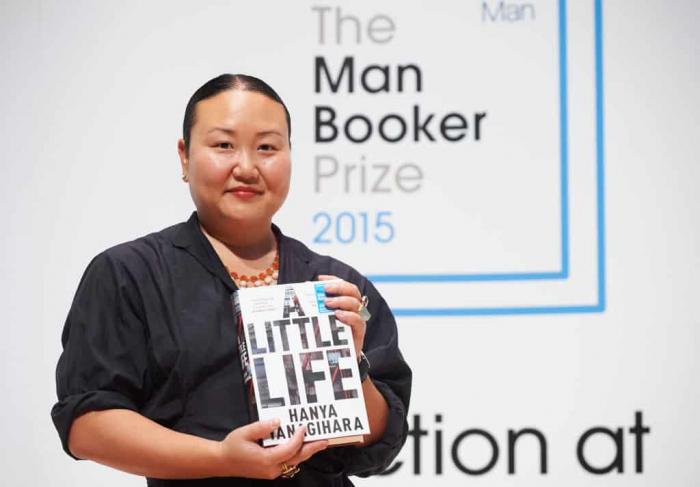

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara is not a book that inspires feelings of apathy. If you’ve read it, then the chances are you either want to devote your entire life to it or you desire to see it thrown into the fiery pits of hell. First published in March 2015, it set the literary world alight with rapturous headlines and declarations of hyper-emotional attachment to its all-consuming pain. Author Garth Greenwell called it ‘the long-awaited gay novel.’ Vox announced that the publishing elites should give the book ‘all the awards.’ It was ultimately shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, the National Book Award, and the Women’s Prize for Fiction. Ivo Van Hove adapted it into a play. The official tote bag became the most coveted reading accessory of the decade. The author appeared on Seth Meyers’ show. Tiktok is obsessed, with users filming themselves sobbing over the latest chapter. Now, it has a tenth-anniversary hardback release (and new audiobook version narrated by Matt Bomer) that has further cemented its status as a modern classic, right as its reputation has started to splinter and face further questions over Yanagihara’s style and themes.

A Little Life follows the story of four friends living in New York as they try to make their way in the big city. There’s Wllem, an aspiring actor, the architect Malcon, artist JB, and Jude St. Francis, a disabled lawyer with a mysterious past. As the novel unfolds, the focus moves exclusively to Jude’s life and we are thrown head-first into the monstrous details of his horrifying existence. Every terrible thing you could possibly imagine happening to Jude has happened: he was sexually abused as a child by the monks who raised him; he was placed in state care where the abuse continued; a man ran over him with his car, leaving him with a limp and in constant pain. As an adult, the trauma has left him barely able to function, and Jude regularly engages in self-harm and suicidal ideation. Over the course of several hundred pages, the reader and Jude’s friends fight for him to get better. Spoiler alert: he never does. There is no escape from his suffering.

Yanagihara was the editor of Condé Nast Traveler with one well-received but low-selling novel to her name when she released A Little Life. It was a book she had wanted to write for a while, and as she told The Guardian, ‘I knew when I started it would be about 1,000 manuscript pages […] I was writing every single night and all weekend and it is not something I necessarily recommend. Though it was an exhilarating experience it was also an alienating one.’ She was determined to tell the story she wanted to, free of editorial meddling and the need to adhere to contemporary tastes. Her editor asked her to tone down some of the more visceral sections, which she refused. ‘I wanted everything turned up a little too high. I wanted it to feel a little bit vulgar in places,’ she explained.

Reading A Little Life is arduous by design. Yanagihara’s prose is often hypnotic. There’s a moment where she describes a self-inflicted cut on Jude’s body as looking like a baby’s mouth, and I have never been able to exorcise that image from my mind. The plot, such as it is, is pure melodrama. Typing out all the stuff that happens to Jude feels like a joke, the ‘yes, and…’ of miserabilism escalating to the point of parody. And yet in practice, it’s so forceful, driving you utterly mad as you sink into a rabbit hole bereft of escape or even a glimmer of light. Yanagihara said she wanted to write a story where the troubled character didn’t get better, and boy did she succeed. She refuses to let anyone off the hook. Not Jude and certainly not the reader. You become enveloped by the pain that Jude has experienced, enraptured by his suffering but complicit in his inability to escape it. The shreds of hope you think you’re getting in the story are wrenched from your hands time and time again.

All of the things that A Little Life fans adore about it are what its detractors loathe, and you can’t exactly blame them for it. This is a tough read whose agonies are not blissful or helpful to many. The book is often labelled as misery porn for the ways it indulges in Jude’s pain and extends descriptions of it over hundreds of pages. Jude is cursed in ways that would make Thomas Hardy characters seem like Dr. Seuss creations. It becomes tedious to be shocked so endlessly with details of his cutting and experiences with CSA. That is the point, of course, but the execution leaves much to be desired by many. In her brilliantly scathing review, Andrea Long Chu compared Yanagihara to a kid with a magnifying glass ‘burning her beautiful boys like ants.’ The masochism of her intent, so ceaseless and relentless, moves from hyper-realist to fetishistic.

Yanagihara is a presumed heterosexual author (she’s never called herself anything else) who is fascinated by stories of gay men. All three of her novels are centred on gay men in some fashion, and with A Little Life, she is particularly intrigued by the sexual and social dynamics of groups of them. Combine this with the dense and frequently poetic quality of Yanagihara’s prose and many critics have questioned the issues of a straight woman turning queer life and trauma into something so aesthetically baroque. In her interview with Seth Meyers, Yanagihara even admitted to asking some of her friends if she could watch them have sex as ‘research’ for the novel.’ That doesn’t help claims that A Little Life is voyeuristic, right?

It’s hard to escape these critiques when A Little Life has now become its own content machine of style and #vibes. The tote bags are still a big deal. While doing sponcon for a brand of cheese, Antoni from Queer Eye made ‘Gougères for Jude’ with Boursin cheese. Valentino’s Spring/Summer 2024 menswear collection took inspiration from the book and included quotes on jackets, bags, and jeans.

I often joke that, if Yanagihara wasn’t a hugely successful author and magazine editor, she would be a fanfiction writer. Specifically, she’d be the author of that one very long fic that is so popular that it has its own fandom and inspires endless Tumblr screeds about its problematic nature. It’d be the fic that everyone fights over, the hurt/comfort slash fic that has no comfort but is so well-written and unrelenting that you have to read the entire thing once you start, be it out of addiction or spite. I don’t say this to belittle Yanagihara or fanfic writers the world over (I’m one myself, sporadically.) But I make the comparison because I feel that Yanagihara’s scope and her view of queerness as a vehicle for narrative exploration and emotional vivisection is similar to the ways that we use fandom to explore our own ideas and desires on the margins.

For me, I find Yanagihara to be a fascinating figure and author. Her first novel, The People in the Trees is one of my all-time favourite books and one I practically fling at people whenever they ask for a recommendation. I like that book quite a bit more than A Little Life for many reasons, one of which is that it’s more narratively controlled a piece of work. It’s clear that Yanagihara is working in tandem with her editor and has a stronger, clearer vision of how this more tangled story will unfold. It shares a lot with her follow-up but it is more a story of the delusions of abusers than the agonies of the abused.

But I cannot deny the sheer power of A Little Life, a book with one hyper-specific agenda that achieves it with obsessive force and a literary magnetism that has attracted countless readers. Admittedly, I have less patience for a story this bleak being turned into merch and luxury fashion, a move that seems to miss the point of Jude’s pain as much as Yanagihara’s most virulent critics claim she herself does. In a more general sense, I’m just flabbergasted and weirdly encouraged by a 700+ page doorstop of agony and ecstasy becoming a mainstream hit. I can’t blame anyone for wanting escape through pain, catharsis through a total denial of it. That’s a legacy that lingers long after the tote bags have been shelved.