Modern Art, True Crime, Feminist Classics: Pajiba June 2025 Book Recommendations Superpost

By Kayleigh Donaldson | Books | June 30, 2025

Confession time: I haven’t had a very book-heavy month. Nothing’s really piqued my interest and the combination of heat, work, and activities (I went to Dublin to see Neil Young! It was my birthday! I went home for a bit!) left me unmotivated to read. So, rather than skip over another month, I thought I’d share a few of my all-time favourite books with you, ones that I feel are furiously underrated and deserve more attention.

Randall by Jonathan Gibbs

Imagine a world where Damien Hirst died before he could become wildly famous. It’s the early ’90s. Thatcherism is over. The new era of Cool Britannia is here and a generation of brash young artists are eager to shake up the system. Step forward Randall, a working-class gadabout who makes headline-grabbing installations that piss off tabloids, inspire public fury, and leave wealthy collectors begging for more. Soon, the art world has a new enfant terrible, but there’s more to Randall than paint and poop (yes, really.)

Randall is my most beloved book that the least people have read. Whenever I bring it up in conversation, everyone responds with, ‘I’ve never heard of that.’ In fairness, it didn’t receive a lot of pre-release hype and was published by an indie house, so I’m not surprised by its niche audience. Still, it’s a book I think about all the damn time, more so now in the era of AI, NFTs and your social media feeds being polluted with cursed images of Jesus’s face made out of shrimp.

Jonathan Gibbs’ alternate version of the Young British Artists era of ’90s culture is pinpoint precise, and its satire so sharp that it almost feels too real. Randall is a motormouth prankster who seems to be playing an extended joke on the art world with his works that deliberately provoke yet lead to multi-million-pound sales and worldwide renown. He makes his name with ‘Sunshines,’ a series of, uh, portraits wherein the subject shows off the toilet-paper remnants of their number twos and they’re painted onto large canvases. Soon, every rich hanger-on and celebrity wants to have their sh*t turned into art. Frankly, I’m stunned that Hirst didn’t actually do something like this in the ’90s.

Gibbs is not only excellent at bringing to life this hyper-specific moment in culture but in creating fake art that would elicit the reactions he writes about. It’s actually extremely difficult to create fake genius, to describe, say, a brilliant painting or film and have the audience believe it’s as mighty as the narrative requires it to be. There’s a reason nobody bought the Lestat of the Queen of the Damned movie as a revolutionary rockstar when the songs were written by the guy from Korn. But in Randall, all of the art described feels like it 100% came from that YBA period and would have inspired the discourse he shows. This is an acerbic novel by a guy who knows this world like the back of his hand but isn’t precious about his portrayals of it. I wish more people would read Randall, if only so I could have someone to talk about it with!

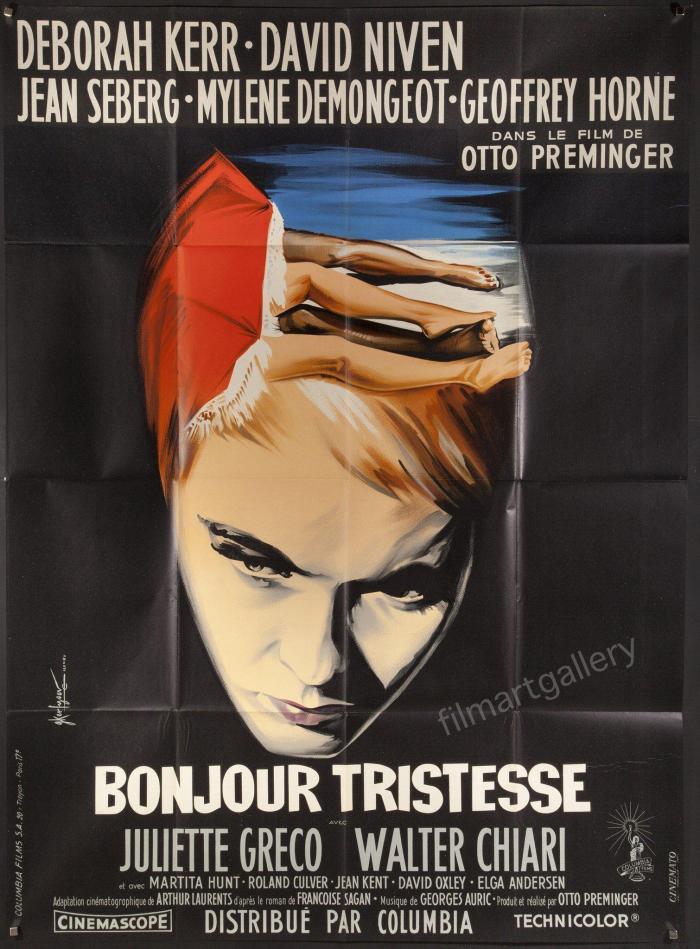

Bonjour Tristesse by Françoise Sagan

(Image via IMDb.)

Françoise Sagan was only 18 when she made her literary debut, Bonjour Tristesse. It was an immediate success and decades later it remains one of the great novels about adolescence and the limits of precociousness.

Cécile wiles away her Summers in a villa on the French Riviera with her father Raymond and his latest mistress, the young and pretty Elsa. It’s a care-free world where Cécile’s biggest worry is finding a good seasonal fling. Things change with the arrival of Anne, a friend of Cécile’s late mother. She’s glamorous, hard-working, and oh-so grown up. But as Raymond finds himself falling for the sensible Anne, Cécile worries that her pampered life is coming to an end.

To say any more would be to give away everything in this short but potent slip of a novella. Some early reviews derided Bonjour Tristesse as vulgar or downplayed Sagan’s achievement as an act of precocity. That does her no favours nor does it give credit to a book that is far more than a prodigy’s project. There’s a stunning aching to the novel that captures the oft-surreal nature of feminine adolescence. You’re on the verge of adulthood and truly believe you’re super mature and ready for anything, but then you’re slapped across the face by reality and reminded that you are indeed just a kid. My favourite stories of teenage life are those that understand this dichotomy (it’s one of the reasons I so love Juno.) Even though Sagan’s book is now over 70 years old, it still feels fresh and urgent, and its ending still shocks.

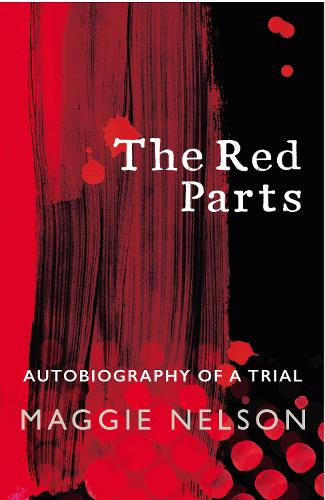

The Red Parts by Maggie Nelson

(Image via Goodreads.)

As I’ve spent most of my career noting, I have a complicated relationship with true crime, one that’s only gotten more tangled and cynical as the genre has exploded in popularity and oversaturated the cultural landscape. So, I treasure the works that prioritize humanity and understanding over leering thrills. Maggie Nelson, a brilliant theorist and writer whose books frequently defy classification, delved into her own family’s past with this one, subtitled Autobiography of a Trial.

In 1969, Nelson’s aunt Jane was murdered. The case went unsolved for decades until a detective figured out decades later that Jane may have been but one of at least six women murdered by the same man. Although she never met her aunt, Nelson was inspired by her story to write Jane: A Murder to ‘let her speak for herself.’ The Red Parts is more about Nelson and her family’s pain as they sit through the long-delayed trial and wait for justice.

It’s a deeply personal book but also perhaps one of Nelson’s most mainstream works. Many of her more famous books, like the stunning theory-memoir of gender, The Argonauts, blend the personal and academic. This is no different but is starker in its prose. Nelson knows that, by returning to this story, she’s opening up a lot of very raw wounds for herself and her loved ones. She’s also stuck in the middle of a cultural obsession with murder and scandal. She wryly notes that Jane’s story is not so juicy to the outside world, even as they pick at minor details that occurred decades prior. Nelson has no easy answers to this uneasy situation because grief is messy and death is a vicious cycle that nobody gets out of alive. As she writes, “For millennia ‘justice’ has meant both ‘retribution’ and ‘equality,’ as if a gaping chasm did not separate the two.”

In the Cut by Susanna Moore

(Image via Goodreads.)

Over the past few years, Jane Campion’s In the Cut, once seen as her most reviled movie, has received a long-overdue critical reassessment. What was previously dismissed as a misjudged attempt at 21st century noir has been embraced as a daring portrayal of rape culture, female desire, and how the latter is often overcome by the former. It’s one of my favourite films, as well as one of my favourite books. If I’m being wholly honest, I think I might like the novel better, and that’s saying something as a Campion devotee.

Frannie Avery is an English teacher who stumbles upon a man receiving oral sex in a bar bathroom. Several days later, a boorish detective, Giovanni Malloy, questions her about the murder of a woman who was last seen in that bar on the same day Frannie visited it. As a violent killer threatens New York City, Frannie falls into a heated sexual relationship with Malloy, an evidently dangerous brute who she is equal parts entranced and repulsed by.

Short, sharp, and shocking, In the Cut more acutely captures the stifling bind of feminine desire in a patriarchal world than any other novel I’ve read. Frannie knows the warning signs and they’re all around Malloy, a handsome bigot who clearly loves being a cop for all the wrong reasons, but being a woman in this society means forever navigating a world of no-win scenarios. Sex is danger and desire is taboo, forever trapping us as we try to figure out the already entangled nature of lust. Moore offers less of a whodunnit than a stark study of predator and prey that subverts the classic tropes of crime noir and erotic thriller.